Exploring community-based resilience systems for women living in poverty: Pointers for humanitarian programming in DRC

This paper is aimed at drawing attention and further understanding of humanitarian actors on community ideas and systems that enhance or hinder resilience of women in the DRC context. It analyses the link between community-based systems and women resilience by providing a conceptual and practical definition of community-based resilience systems and how the systems contribute to women resilience. The paper recommends for a community, territorial, provincial and national dialogue on resource redistribution with the objective of developing community resource distribution framework. It also recommends that, in designing humanitarian intervention to build resilience, it is important to take into consideration key characteristics of minority group and their voice to ensure that the strategic needs of all those targeted are catered for in the interventions.

Introduction

The history of DRC has been marked by conflict, underdevelopment, misgovernment and a sustained humanitarian crisis. The country year after year ranks at the bottom of the Human Development Index. Over the past two decades, large-scale humanitarian response has become a constant in DRC. Chronic waves of violence in the country have resulted in the repeated internal displacement of about 5.2 million persons, the second largest number of internally displaced persons in the world (WFP, 2021). The DRC also hosts 527,000 refugees from neighboring countries. Armed conflict and violence, epidemics, natural disasters, and the socio-economic impact of COVID-19 have considerably exacerbated already existing vulnerabilities, in a context marked by a structural lack of access to essential services. As a result of these complex and deep humanitarian crisis, 19.6 million people will need assistance and protection in 2021, an increase from 15.6 million at the beginning of 2020.

There is a high prevalence of severe acute malnutrition among children between ages 6 to 59 months. Concerns have also been raised over the prevalence of protection risks and the fact that most provision of social services and building of infrastructure have been affected by conflict. The COVID 19 pandemic has also exposed women, adolescent girls and children to additional agricultural and field work and an increase in unpaid work responsibilities, increasing their risk to the disease transmission. It has heightened the risk of girls engaging in prostitution in order to contribute to income for their families which in turn puts them at risk of sexual and physical violence (WFP, 2021).

While statistics are hard to come by due to the nature of the DRC, there are estimates that nearly 80% of the country’s population lives in extreme poverty (The Borgen Project, 2020). While Congolese women constitute 53% of the DRC population, more than 60% of Congolese women live below the poverty threshold against 51.3% of men. Violence against women is endemic owing to various factors including discriminatory attitudes towards women, outdated customs, conceptions of sexuality, weak legal and judicial systems, culture of silence of victims and impunity of perpetrators (Government of DRC, 2017). In 2018, more than 35,000 cases of sexual violence were recorded. Gender norms restrict women’s access to resources and assets – for example, assets obtained within marriage are registered under the husband’s name, and regarded as assets of the husband, his parents and brothers. By law, women can inherit but they cannot own a house due to prevailing social norms. Women are not legally recognized to be heads of households, and there is no prohibition on discrimination based on marital status in access to credit. Young people and IDPs have limited access to sexual and reproductive health services. About one in every 100 births causes the death of the mother. Despite this, adolescent sexual and reproductive health issues are politically and socio-culturally sensitive.

Humanitarian response

Recurring crises affect an estimated 15 million people (20 percent of the country’s population). Insecurity, poor road networks and logistical constraints restrict humanitarian access to populations in need in numerous remote areas (UN OCHA, 2015). Despite sustained humanitarian engagement, recent studies on humanitarian response in DRC conclude that little has been done to build resilience in the country and specifically to increase the autonomy of IDPs especially women in a protracted conflict. This calls for a rethink of how external resources are used to engineer traditional ideas and systems around resistance to shocks especially by women who are most affected by crisis. Humanitarian programming should explore programming models that strengthen individual women and their communities’ ability to absorb shocks and survive unforeseen crises.

Motivation and methodology

This paper is to draw attention and further understanding of humanitarian actors of community ideas and systems that enhance or hinder resilience of women in the DRC context. The paper analyses the link between community-based systems and women resilience by providing a conceptual and practical definition of community-based resilience systems and how the systems contribute to women resilience. It also examined determinants of individual and community resilience based on experiences in the DRC.

The findings will enable humanitarian actors including communities to appreciate the role of community-based systems in building women resilience especially in communities affected by crisis. This will in effect provide insights in designing humanitarian programming that promotes successful resilience-building interventions for women taking into consideration local systems, assets and capabilities. According to CESVI (2019), resilience is a crucial issue in humanitarian programming, especially in fragile and conflict-affected areas like the DRC.

A systematic literature review of definitions of community-based resilience systems as it relates to women was undertaken. Primary information was also collected from 50 people in the Kinsenso Commune and Kabare Territory of the DRC based on the conceptual framework of community-based systems and women resilience modelled for this paper. Kisenso is a peri urban municipality (commune) in the Mont Amba district of Kinshasa. It is one of the 24 communes of the Kinshasa Province with a population of over 400,000 people. Kabare Territory on the other hand is a rural territory located in the far eastern Congo on the western shores of Lake Kivu with a population of 37,034 (2012 est). These two areas present a sample of population with characteristics depicting urban, peri urban and rural of the DRC. The two areas are selected because of the striking characteristic of the Democratic Republic of Congo where poverty is almost as high in urban (62.5 percent) as in rural (64.9 percent) areas, and smaller cities tend to be much poorer than the largest cities of the Democratic Republic of Congo (World Bank, 2018).

The primary sources included the outcome of structured interviews with 4 relevant agencies, 30 representatives of womens groups, 6 community leaders, 6 representatives of youth groups and 4 local authorities. Descriptive analytical method was employed to analyse information collected in order to determine the appropriateness and efficacy of community-based systems in promoting women resilience.

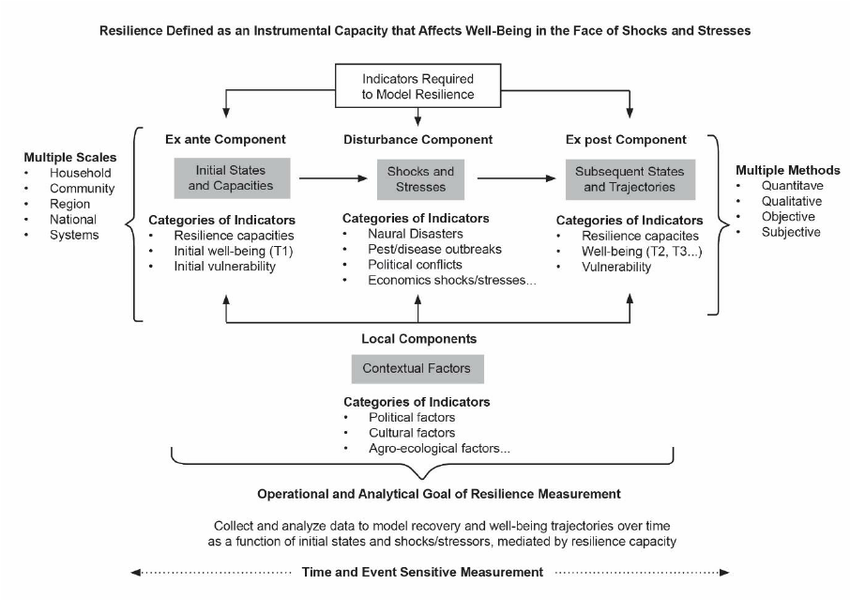

DEFINITIONS OF RESILIENCE: Resilience has been described as ‘the capacity of people or “systems” to cope with stresses and shocks by anticipating them, preparing for them, responding to them and recovering from them’ (Adam and Simon, 2012). On the other hand, resilience can also be defined as the capacity of a system, community or society potentially exposed to hazards to adapt by resisting or changing in order to reach and maintain an acceptable level of functioning and structure (UNISDR, 2005). The IASC (2015) argued that resilience is the instrumental capacity that affects wellbeing in the face of shocks or stresses as depicted on figure 1.

Resilience is broadly accepted by aid agencies and understood as the ability to withstand and recover from shocks (Sarah and Veronique, 2014). Several donors and aid organisations like UN agencies, ActionAid, Oxfam, Save the Children, DfID and European Commission have their own resilience policies, strategies and approaches which influence the way they build resilience of persons of concern. Its important to recognise that persons of concern especially women are important stakeholders in resilience programming. They are individuals, groups, and communities that are directly or indirectly affected by a humanitarian crisis. They include internally displaced population, refugees, returnees, host families, people living with disabilities, older people, pregnant and lactating women, unaccompanied and separated children, vulnerable women, men and children who are most at risk.

Figure 1:

Capacity in the face of shocks or stresses

Source: IDS, 2015

About 52% (26) participants interviewed during the development of this paper revealed that resilience is the ability to protect oneself and family whilst 22% responded that resilience is the ability to protect properties in case of disaster. 55% of female interviewed responded that resilience is the ability to protect oneself and family and 42% of male interviewed revealed that resilience is about the ability to protect properties in case of disaster or shocks. 50% of male respondents interviewed from Kisenso revealed resilience is about ability to protect properties in case of disasters. Whilst female respondents were concern about live saving during shocks and disasters, male respondents were concern more about properties that will cater for families after disasters or shocks. Its important to note that over 50% of respondents between the ages of 16 to 55 years responded that resilience is the ability to protect oneself and family. The various definitions of resilience point to some core elements resilience including capacity of people or systems to cope with stresses and shocks, capacity of people, community or society potentially exposed to hazards to adapt, ability to protect oneself and family, ability to claim rights and ability to participate in decision making.

Resilience is therefore the capacity to organize oneself or a community in order to reduce the impacts of natural and manmade hazards by protecting resources such as lives, livelihoods, homes, assets, services, and infrastructure. It include capacities to advance those development processes, social networks and institutional partnerships that strengthen its ability to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from disaster (Maureen and Suranjana, 2011).

Women living in communities affected by crisis are consistently identified as one of the groups most vulnerable to manmade and natural hazards. Their meagre asset base, social marginalization, lack of mobility and exclusion from decision-making processes compound the vulnerabilities they experience. It is important to recognize that women’s vulnerabilities are embedded in social, economic and political processes—and the development gaps that reproduce them. However, development processes can empower women living in poverty to transform the living conditions of their families and communities and to reverse these vulnerabilities. Women living in poverty are experts in resilience. They are proficient in adapting to changing social and natural environments, organizing to collectively address problems, drawing on traditional knowledge and improvising skills to face difficulties. Though the enormity of the stresses and shocks often overwhelms their efforts. Poverty and marginalization do not necessarily mean passivity in the face of disasters, extreme events or development challenges (Maureen and Suranjana, 2011).

Community-based systems and women resilience model

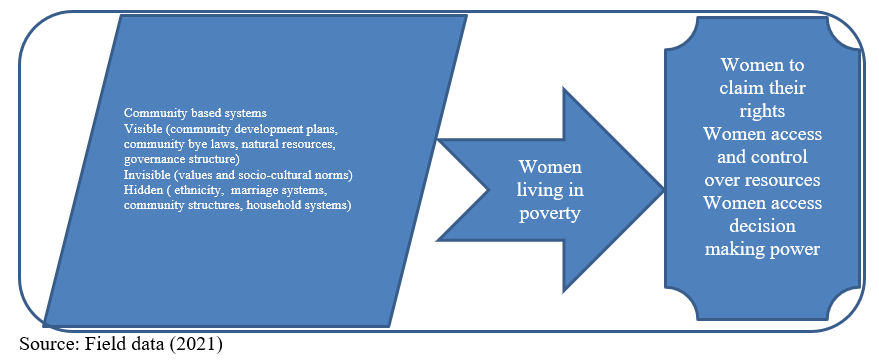

This article is based on a conceptual model that recognizes three interrelated and interdependent themes to clearly present relationships between manifestations of community systems, women living in poverty and resilience.

Figure: 2

Community-based systems and women resilience model

|

Community based systems Visible (community development plans, community bye laws, natural resources, governance structure) Invisible (values and socio-cultural norms) Hidden ( ethnicity, marriage systems, community structures, household systems) |

The Community-based systems and women resilience model as shown on figure 2 depicts the differential effects of community-based systems on women resilience. The conceptual model defines community-based systems as manifested through visible, invisible and hidden systems in the community. Women living in poverty is also defined to include women IDPs, widows, smallholder farmers, women refugees and returnees, adolescent girls and women from ethnic minority. Women resilience is defined as ability of women to claim their rights, access and control over resources and access to decision making power. The model has community-based systems as the independent variable whiles women resilience is the dependent variable.

Community-based systems and women resilience

Communities have over the years developed systems based on their societal norms, assets and capabilities to respond and cope with stress and shocks. These systems vary from community by community based on their uniqueness, context and history. Community systems that moderate women resilience are embedded in geo-political and socioeconomic processes and the development gaps that reproduce them. These are systems that protect the community from exposure, vulnerabilities and risks. The systems are expected to facilitate processes that enable women to realise their full potential and provide the first 24-hour responses and relief in case of disaster. Respondents interviewed revealed that communities have traditional structures such as self-help groups that strengthens women’s resilience within the community.

Visible community-based system

Visible community-based systems are observable systems which include formal rules, structures, authorities, institutions and procedures of decision making in the community. It is manifested through community development plans, community bye laws, natural resources, governance structure. This system defines community level decision making processes to serve the needs and rights of people and the survival of the entire community. Naturals resources, community development plans and local governance structures are contributing to resilience when its contributing to fight against inequalities by involving women. These are critical elements of visible community-based resilience system. In the Kisenso Commune, 60% of women revealed that there is an efficient contribution of visible system to women’s resilience because women are considered in the implementation of the plans of the commune. In the Nyiragongo area, 70% of respondents revealed that though development plans exist, there is minimal involvement in its development and implementation. 66% of all respondents revealed that there is conscious effort to involve women in governance structures to enhance women participation in leadership and decision making. Community structures like development committees, self-help groups, education committees, development committees and youth groups have some of their leaders being women. All these practices contribute to build women resilience by building their capacities, increasing their confidence as well increasing self-awareness and self-worth. On natural Resources, one of the most important mentioned is land. This is almost an impossibility for women living in poverty in the Kisenso area where land is very scarce due to its closedness to Kinshasa, the national capital. National laws and policies had little impact on the rural women in terms of access to land. Local norms tend to discriminate against women, undermining their secure access to land and enforcing women’s dependence on men (husbands or male relatives) who have rights to land. Most women therefore depend on a male relative's owned or rented land under ‘traditional’ frameworks. (Women for women, 2021).

Although shocks strike without discrimination, due to the lack of gender-integration in current development approaches and imbalanced access to resources and uneven division of responsibilities, the resilience of women and girls is particularly tested. When shocks occur, women are often left alone to cope with children balancing care and seeking productive engagement, all of which while they are usually deprived access to many resources and opportunities. Gender-based inequalities in access to and control of productive (including land) and financial resources continue to slow down agricultural productivity and undermine resilience efforts. With rising uncertainty caused by climate and other rural stressors, households need resources to cope and adapt to shocks and livelihood challenges. Women tend to have less access to these necessary resources for adaptation (UN Women, 2016). The visible community-based systems must work to reduce women and girls exposure gender-specific barriers which exacerbate the challenges women already face in the context of general and chronic vulnerability.

Invisible community-based systems

Invisible systems in the community manifest itself through community values and socio-cultural norms. It shapes the meaning and what is acceptable. It is the fundamental unspoken and unwritten ideology upon which the community is built. It influences how individuals think about their place in the community. This system outlines beliefs, sense of self and acceptance of the status quo –even their own superiority or inferiority. It defines the processes of socialisation by defining what is normal, acceptable and safe.

Traditional or customary laws and practices have the biggest influence as unwritten rules that guide beliefs and behaviours in communities (women for Women, 2015). 80% of women respondents’ from both Kisenso and Nyiragongo revealed that socio-cultural values do not strengthen women’s resilience. The invisible system only contributes to widen gaps between women and the community thereby crowding out opportunities for them to access productive resources as well as participate in taking decisions that affect them at both household and community level. It strengthens inequalities in the community and perpetuate processes that relegates women to the background. 50% of male respondents from Nyiragongo support these views from women. 20% of female respondents who are above the age of 55+ revealed that though the intentions behind some of the societal norms and values are good, men rather use them to the disadvantage of women. Women continue to be largely marginalized, often due to discriminatory practices, attitudes and gender stereotypes, deeply rooted in patriarchal systems, that result in the lack of gender sensitive legal frameworks, policies and programmes; limited access to resources; lack of a political voice; and disproportionate power relations between the genders in households and communities. In times of shock, women’s role in providing food and care for the family becomes more critical, while women’s challenges become harder due to existing gender-specific barriers (UN Women, 2016). It is important to however note that there is an ongoing transformation of some of these practices including having men leading the campaign for social justice. Women are gradually being accepted to be involved in managing the family resources and community members who defend gender equality are being encouraged by other community members.

Hidden community-based systems: The hidden community-based system sets community agenda with which resources are distributed and owned, and decisions are made. It influences how the visible system plays out by excluding and devaluing the concerns and representation of other less powerful groups in the community. It is manifested through ethnicity, marriage systems, community structures. This system is a conduit for discrimination based on traditional practices and succession, impunity contrary to laid down laws, exclusion and low involvement of women. Just like the invisible system, respondents are of the view that this system contributes negatively to building resilience of women. 60% of respondents indicate that hidden systems are subject of more conflict in the community. It does not allow women to explore their full potential and makes them perpetual dependents. It is the system through which the retrogressive and unfair practices shapes and frame opinions of the community. 50% of female respondents above the 55+ indicate that it is a system that distances the real intensions of community values from how it is used in modern days. Though 70% male respondents support this view, they also attributed the influence of this system in the communities to women. According to them, some of these practices are led by women through which some have become resilient through the resources and power they have.

Determinants of resilience

Sonny et al., (2017) identified an array of determinants or elements that have been proposed within the general notion of resilience. Factual knowledge base, collective efficacy and empowerment, and training and education have been proposed as useful within the element of local knowledge in order to mitigate vulnerabilities caused by how an individual or community understands risks. The positive effects of connectedness and cohesion within the element of community networks and relationships have been seen, especially in recent times, to help people deal with uncertainty after a disaster. Effective communication, whether risk or crisis communication, was proposed as important in helping a people and community to articulate, coordinate and understand the risk and impact of disasters. Health services were clearly relevant for a disaster-affected community, though a lack of knowledge of a community’s pre-existing issues among its residents and/or difficulty in delivery of quick, high-quality care were identified as key areas of difficulty to guard against.

Similarly, the fair distribution of resources may help communities in the short term, while economic investment was generally seen as a longer-term intervention to promote resilience. Preparedness overlapped with the elements of local knowledge and communication but was typified by an emphasis on specific actionable activities. Lastly, mental outlook arguably has the most potential to build resilience within a community through a focus on sub-elements such as hope and adaptability (Sonny et al., 2017).

This paper distinguishes the determinants of community resilience from individual resilience to avoid sameness in humanitarian programming. The factors that determine resilience of individuals include sex, access to resource, access to basic services, socio-cultural norms, participation in community development processes. On the other hand, factors that determine resilience of community are identified as visible community systems, invisible community systems and other factors including category of community (rural or urban).

Resilience of individuals

48% of respondents revealed that access to resources is a major factor that determine resilience of individual. However, only 46% of female who were interviewed agreed with this view. 14% of respondents from Kisenso responded that access to basic services is a key determinant of resilience whilst another 14% responded that there are other factors including category of community aside sex, access to resources, access to services, socio-cultural norms of community and participation in community development processes. The location of the community within the province or the territory influences resilience through exposure to natural disasters like volcano. 57% of those who responded that services are key determinants of resilience are widows/widower. It is important to note that these are people with very limited opportunities and might have lost their spouses through conflict.

12% of respondents also revealed that socio-cultural norms of community are key determinant of resilience of an individual. For those who responded that access to resources is a key determinant of individual resilience, they argued that ability to access critical resources like land, shelter, money, water, livestock and food reduces levels of vulnerabilities of the individual. With this, the individual can withstand the hazard and cope without using any negative coping mechanisms. In terms of access to social services, emergencies and disasters expose individuals to different forms of vulnerabilities. Having access to basic services will therefore reduce the risk of vulnerability thereby making the individual resilient. These services include medical, mental and psycho-social, education, transport, sanitation, hygiene and water.

According to Dreze and Sen (1989), vulnerability could be reduced if a household’s entitlements were sufficient to enable it to cope with the stress of inadequate food stocks. The observation was that a positive relationship existed between entitlements and the resilience of an individual or community confronted with ecological or economic risks, and social assets such as networks were as important as material goods in reducing vulnerability (Bohle 2001). Watts and Bohle (1993) extended this analysis, embedding entitlements in the political economy, where empowerment, or the ability to shape the political economy, in turn shaped entitlements.

It is interesting to note that only 2% of respondents revealed that sex is a determinant of resilience. This is to confirm that resilience relies upon not only the individual factors, but also is heavily influenced by the availability of services and supports in the environment and an individual's ability to access them. Some examples of supports important to resilience include a positive relationship with a caring adult, a community to engage with, as well as services that are provided in a meaningful manner (Nettles et al., 2000).

Community resilience

Though the concept of ‘community resilience’ is almost invariably viewed as positive, being associated with increasing local capacity, social support and resources, and decreasing risks, miscommunication and trauma (Communities Connected Consultancy, 2018), this paper outline core factors that promote or hinder resilience of a community.

62% of respondents revealed that community’s resilience depends on its visible community systems like development plans, by laws, natural resources and governance structure. 65% of these respondents are female. They posit that the visible systems make it possible to establish early warning systems, integrate disasters in development plan and establish local governance structures which recognizes people with expertise in disaster management. This confirms Sonny et al (2017) position that community resilience has to do with having a responsive and collective action of local support to help the community after an incident. This is also buttressed by how United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction defined community resilience as “ability of a system, community, or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate to and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner (UNISDR, 2012)

36% of respondents have recognized invisible community systems as a determinant of community resilience. They observed that people are more empowered to help one another after a major disturbance in communities. Since people are regularly involved in each other’s lives as a result of social norms and culture, persons affect ted by disaster are able to access social support which is critical in the first 24 hours of disasters. This social connectedness also help in emergency preparedness action which requires collective action. Given the role of women in emergency response as the first 24-hour respondents, the social connectedness gives them confidence and feel valued and respected for what they do. According to L. J. Hanifan (1916), ‘’the community will benefit by the cooperation of all its parts, while the individual will find in his associations the advantages of the help, the sympathy, and the fellowship of his neighbours” (WREMO, 2012)

Conclusions and recommendations

Conclusions

Visible community-based systems enable women to access their rights to live a life of dignity. It expands opportunities for women to access resources and be part of decision making. Even though information analysed in this paper revealed that 60% of female interviewed in Kisenso revealed efficient contribution of visible systems and 70% of respondents from Nyiragongo revealed that there is minimal involvement of women in the development and implementation of development plans, there is an agreement that conscious efforts are being made to enhance women participation in leadership and decision making.

While 20% of female respondents who are above the age of 55+ revealed that though the intentions behind some of the societal norms and values (invisible system) are good, 80% of female respondents revealed that sociocultural values do not strengthen women’s resilience. The invisible system only contributes to widen gaps between women and the community. It deprives them from claiming their rights including access to and control over resources and access decision making power. However, this system is recognised to support community’s resilience or bouncing back better in case of emergency.

Hidden systems in the community are seen as a major source of conflict. 50% of female respondents above the 55+ indicate that it distances the real intensions of community values from how it is used in modern days. 70% male respondents revealed that women have also used the hidden systems in the communities to become powerful in terms of access and control over resources and decision making.

It is important to distinguished factors that determine resilience of individual from the ones that determine resilience of communities. The factors that determine resilience of individuals include sex, access to resource, access to basic services, socio-cultural norms, participation in community development processes. On the other hand, factors that determine resilience of community are identified visible community systems, invisible community systems and other factors including location of the community.

Whilst 57% of those who responded that services are key determinants of resilience are widows/widower, only 2% of respondents revealed that sex is a determinant of resilience.

62% of respondents revealed that community’s resilience depends on its visible community systems like development plans argue that visible systems make possible to establish early warning systems, integrate disasters in development plan and establish local governance structures which recognizes people with expertise in disaster management.

Recommendations

There is the need for community, territorial, provincial and national dialogue on resource redistribution at all levels with the objective of developing community resource distribution framework. This will provide culturally sensitive insights on how resource should be distributed to increase resilience of individuals in communities.

In designing humanitarian intervention to build resilience, it is important to take into consideration key characteristics of minority group and their voice to ensure that the strategic needs of all those targeted are catered for in the intervention. Absolute figures might look small in some cases, it should not be overlooked.

Communities have confidence in how visible systems function. This should not be taken for granted. Humanitarian actors should be conscious of this system in resilience building interventions. Resources should be invested by government to target these systems and make them more effective and recognizable. Any attempt to reform this system without the leadership of communities will fiercely resisted.

In humanitarian programming, interventions should aim at deconstructing or transforming hidden and invisible community-based systems. Given the work done by humanitarian actors and other actors in development, it is important to do a critical review of interventions implemented to transform traditional norms and values that relegate women to the background. It is important to however note that these systems are critical elements of societal set up and need to be engaged with caution and sensitivity. To avoid the debate of ‘we and them’’, positive masculinity methodology should be integrated in these interventions.

For humanitarian programming to build resilience, it is important to distinguished interventions aimed at building individual resilience from interventions aimed at building community resilience and how the two interrelate and reinforce each other.

Author: Yakubu Mohammed Saani

References

Adam, P. and Simon, L. (2012). A conceptual analysis of livelihoods and resilience: ‘addressing

the ‘insecurity of agency’. Humanitarian Policy Group (HPG) Working Paper, Overseas Development Institute.

Bohle, H. G. (2001). Vulnerability and criticality: Perspective from social geography.

International Human Dimensions Programme on Global Environmental Change. http://www.ihdp.unibonn.de/html/publications/update01_02/IHDPUpdated01_02bohle.html.

CESVI (2019). The value of resilience in fragile communities. CESVI Participatory Foundation and NGO Italy.

Communities Connected Consultancy (2018). Approaches to community resilience.

Communities Connected Consultancy Limited.

Drèze, J., and Sen, A. (1989). Hunger and Public Action. Oxford University Press.

Government of the Democratic Republic of Congo (2017). Report To The African Commission

On Human And Peoples’ Rights On The Implementation Of The African Charter On Human And Peoples’ Rights From 2008 To 2015. http://www.achpr.org/states/democratic-republic-of-congo/.

IASC. (2015). Multi-year strategic response plan. Guidance. IASC.

IDS. (2015). Working paper. Volume 2015 No 459. IDS.

Maureen, F., and Suranjana, G. (2011). Leading resilient development. Grassroots

Women’s Priorities, Practices and Innovations. United Nations Development Programme and GROOTS International.

Nettles, S., Mucherah, W., and Jones, D. (2000). Understanding Resilience: The Role of Social Resources. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk. Pages: 46-70.

Sarah, B. and Veronique, B. (2014). Towards a resilience-based response to the Syrian refugee crisis: A critical review of vulnerability criteria and frameworks. UNDP.

Sonny, S. P., Brooke, R., Richard, A., and James, R. (2017). What Do We Mean by 'Community

Resilience'? A Systematic Literature Review of How It Is Defined in the Literature.

The Borgen Project (2020). Ongoing Poverty in Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Borgen Project.

UN OCHA (2015). Humanitarian Action Plan, 2015. UN OCHA, DRC.

UN Women (2017). Regional Sharefair on Gender and Resilience. UN Women.

UNISDR (2012). Disaster Risk and Resilience Thematic Think Piece. United Nations.

UNISDR. (2004). Action 2005-2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters. United Nations.

Watts, M. J., and Bohle, H. G. (1993). The space of vulnerability: The causal structure of hunger and famine. Progress in Human Geography Pages:43–67.

WFP DRC (2021). External Situation Report. Pages: 21 – 29.

Women for Women International (2021). Women's access to land in eastern DRC. Women for Women International.

World Bank (2018). Democratic Republic of Congo Urbanization Review Productive and Inclusive Cities for an Emerging Democratic Republic of Congo. The World Bank.

WREMO (2012). Community Resilience Strategy: Building Capacity: Increasing Connectedness - Fostering Cooperation. Wellington Region Emergency Management Office.