The impact of race and gender on the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada

The objective of this research study is to examine the impact of race and gender on the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada using the Integrative Literature Review research method. The position of immigrant women in the Canadian labour market is influenced by gendered and racialized institutional policies, practices and accreditation systems leading to underemployment and unemployment of immigrant women. There are various factors including age, official language fluency, education level, access to social and cultural capital, country of origin and immigration status that influence the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada. This study, however, focuses on the dimensions of race and gender as these significantly impact immigrant women seeking to integrate into the Canadian labour market. This study, therefore, recommends that race and gender be particularly taken into consideration when examining and understanding the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada.

Research question:

- How does gender influence the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada?

- How does race affect the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada?

The objective of this research study is to examine the impact of race and gender on the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada using the Integrative Literature Review research method. The position of immigrant women in the Canadian labour market is influenced by gendered and racialized institutional policies, practices and accreditation systems leading to underemployment and unemployment of immigrant women. There are various factors including age, official language fluency, education level, access to social and cultural capital, country of origin and immigration status that influence the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada. This study, however, focuses on the dimensions of race and gender as these significantly impact immigrant women seeking to integrate into the Canadian labour market. This study, therefore, recommends that race and gender be particularly taken into consideration when examining and understanding the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada.

Introduction

The Canadian population is witnessing a rapid increase in the number of immigrant women. In 2021, a total of 113,036 immigrant women arrived in Canada (Statista, 2021). There has been an increase in the number of racialized immigrant women coming to Canada over recent decades. 84% of these women have identified as visible minorities or racialized in 2016 (Statistics Canada 2016). According to Women in Canada: A Gender-based Statistical Report Canada, 49% of recently immigrated women have a university degree or certificate at the graduate or postgraduate level, compared with 23% of their Canadian-born counterparts. Close to 49% of immigrant women of core working age (25 to 54) with a bachelor's level education or higher are employed in positions that do not typically require a degree. Of those in the core working age group who hold a bachelor's level degree or higher, 60% are employed in positions that do not match their education level (Statistics Canada, 2016).

The issues faced by immigrant women are not uniform for all immigrant women. Immigrant women are a heterogeneous group and their labour market experiences are unevenly shaped by factors such as class, education level, age, race, immigration stream, country of origin and official language fluency (Premji & Shakya, 2017; Jagire, 2019). There is, however, a significantly pronounced gendered and racialized dimension to Canada’s income gap and unemployment and underemployment rates that particularly affect immigrant women’s position in the Canadian labour market. When immigrant women are employed, they are more likely to be underemployed, working in part-time, precarious, and poorly remunerated jobs that are not commensurate with their training and education (Jagire, 2019). Immigrant women continue to be concentrated in a narrower range of feminized occupations and earn lower wages across all occupational groups and levels of education. Immigrant women, particularly racialized immigrant women, are overrepresented in low wage, precarious workplaces. Racialized immigrant women are also often othered both for their racialized status and for the perception that they are more than willing to work at wages below those paid to white workers (Jagire, 2019; Jeeva, 2018; Noack & Vosko, 2011). Gender, nationality, immigrant status (e.g., dependent visa status) and systemic racism play significant roles in the deskilling process that immigrant women experience in the Canadian labour market (Creese & Wiebe, 2009; Jagire, 2019; Meares, 2010).

Research Objective

The objective of this research study is to examine the impact of race and gender on the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada.

Research Questions

The research questions that this study seeks to answer are as follows:

- How does gender influence the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada?

- How does race affect the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada?

Methodology

The methodology used in this research is the Integrative Literature Review (ILR). This methodology not only offers new insights, but also provides summaries on topics that are being researched. Integrative Literature Review goes beyond analyzing and synthesizing primary research findings as it allows researchers to include other resources such as opinions, discussion papers and policy documents (Lubbe et.al, 2020). The articles, policy papers and reports that were chosen for inclusion in this study were identified by perusing through statistical websites such as Statistics Canada and Statista Research Department, peer reviewed journals and books under Google Scholar database, SAGE journals database, Ethnicity & Health journal database, Journal of International Migration and Integration database, Ethnic and Migration Studies journal database, and policy reports and discussion papers from Social Research and Demonstration Corporation, Skills Next and Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. The following key words were used to search for appropriate literature:

Immigrant women, gender, race and labour market in Canada

Visible minority immigrant women and labour market in Canada

Integrative Literature Review

Gender and labour market position of immigrant women in Canada

Immigrant women’s labor market experiences tend to be much more challenging than immigrant men’s experience in the Canadian labour market (Kofman & Raghuram, 2015; Meares 2010). Immigrant women experience significant difficulties than immigrant men in continuing with their former careers because of an unequal sexual division of labour within the home, which is often amplified by a loss of familial and social support post immigration. The conflicting demands of household responsibilities and paid work commitments limit employment options for immigrant women resulting in deskilling, labour market marginalization and downward occupational mobility (Meraj, 2015). The gendered dimensions of immigration policies also put immigrant women at a disadvantage. The ideological construction of competencies and skills in current immigration policies and practices recognizes stereotypically male-dominated occupations as skilled professions, such as, engineering, IT, etc., privileging men as principal applicants and providers while relegating women to dependant status and as trailing spouses (Killian & Manohar, 2016).

Immigrant women in Canada mostly have access to social enterprise programs or subsidized programs in largely gendered fields, such as catering, with no real employment prospects because the skills developed and experience gained are not particularly valuable in the Canadian labour market (Senthanar, MacEachen, Premji & Bigelow, 2020). For instance, current job market trends show sales and service, trades and transportation occupations as having the highest vacancies (Statistics Canada, 2018) but current employment programming for immigrant women are not geared towards these areas. A recent study by Senthanar (2019) on the work integration experiences of Syrian refugee women highlights that these women were open to different employment opportunities that made use of their skills and experience, and also to gain Canadian work experience, but were instead directed to deskilled, gendered positions.

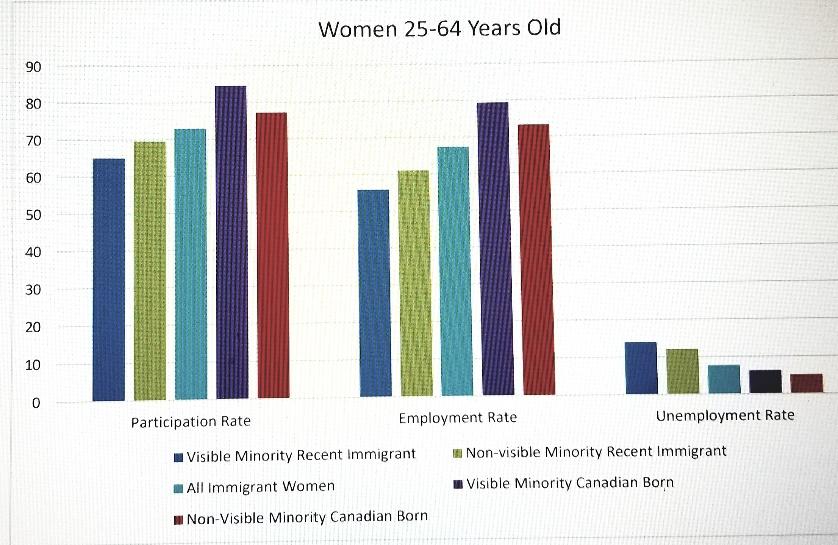

Table 1 demonstrates labour market participation for women (25-64 years old), where recent visible minority immigrant women have the lowest labour market participation rate, lowest employment rate and highest unemployment among the five groups of women included in the chart.

(Source: Career Pathways for Visible Minority Newcomer Women in Canada, Feb 2019)

Race and labour market position of immigrant women in Canada

A racialization is an act of power and a relational process that both distinguishes and creates groups of people as racialized Other and, simultaneously, a racialized We (Behtoui et. al, 2017). Racialization affects visible minority immigrant women to a higher degree than Canadian-born women and men of both visible minority and non-visible minority status (Bevelander & Pendakur, 2014; Premji & Lewchuck, 2014). Labour market experiences of racialized immigrant women are characterized by salary discrepancies, lack of benefits, and negative attitudes reflected in the actions and behaviours of others (Offermann, Basford, Graebner, Jaffer, De Graaf & Kaminsky, 2014). These labour market realities also highlight the fact that, regardless of their education and work experience, immigrant women and particularly racialized immigrant women tend to be forced into gendered occupations characterized by low wages, little or no work benefits or job stability (Premji et al., 2014), affording fewer opportunities for advancement in the workplace and lesser avenues for securing economic and upward mobility (Panikkar, Woodin, Brugge, Hyatt & Gute, 2014). They often work in jobs that are not considered highly skilled and these jobs offer low pay and poor working conditions. What is more, the positions that they hold tend to be marginally related or totally unrelated to their field of training and expertise (Panikkar, et al., 2014); for example, teaching and healthcare professionals (e.g doctors) working as personal support workers or daycare assistants, doctors working as cleaners, and forestry experts working on commission as insurance brokers (Premji et al., 2014).

Racialized immigrant women also tend to lack the social capital than Canadian-born women and men. These connections could be family, peers, acquaintances, and professional contacts who have significant influence because they act as networks assisting with employment and other settlement needs (Hanley, Mhamied, Cleveland, Hajjar, Hassan, Ives, Khyar, & Hynie, 2018). Thus, the networks of racialized immigrant women tend to remain limited to others in similar circumstances as them and to similar ethnic groups. This lack of social capital makes it difficult for them to improve their employment outcomes, and they often remain in precarious and low-skilled positions (Senthanar, 2019).

Workplaces are not race-neutral. Racialization in workplaces has an impact on immigrant women when it comes to confronting gender stereotypes as racialized immigrant women are often considered as tokens where their achievements are attributed more to their race than to their credentials (Flores, 2011; Hanley et. al, 2018). The racial hierarchies and inequalities in the workplace are often maintained by the actions and non-actions of people who are in positions of authority as they have “control over goals, resources, and outcomes; workplace decisions such as how to organize work; opportunities for promotion and interesting work; security in employment and benefits; pay and other monetary rewards; respect; and pleasures in work and work relations” (Acker, 2006: 443). Such control leads to lack of power in the workplace and silencing of workers who feel less powerful than others, particularly women and racialized workers (Acker, 2006; Behtoui & Neergaard, 2010; Behtoui et.al, 2016; Boréus & Mörkenstam, 2015; Morrison, See & Pan, 2015).

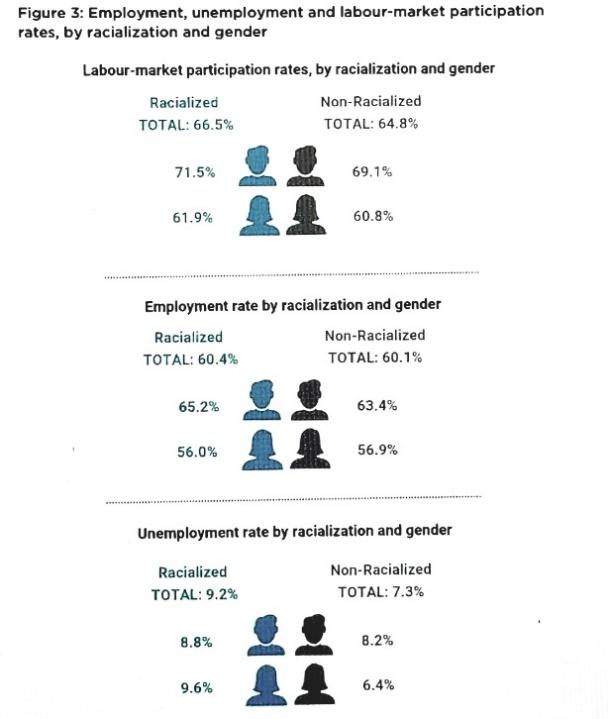

Figure 2 demonstrates racialized women, including racialized immigrant women working and actively looking for work in Canada yet their unemployment rates are higher, thereby experiencing the most disadvantageous Canadalabour market outcomes.

(Source: Ng & Gagnon, 2020)

Discussion and Recommendations

Canada has a history of ethnic and racial bias that shows preference for European immigrants over immigrants from racialized source countries (Chatterjee, 2015). In Canada, racialized power structures are pervasive and issues of race and racism are alive in the settlement, employment and integration of racialized immigrant women. This is reflected in the fact that despite immigrant women being trained in professions associated with the highest incomes in the Canadian labour market (e.g., engineering), they tend to be most underpaid relative to native-born non- visible minority Canadians (Jeeva, 2018; Meares 2010). Scholars have stated that the inequitable, discriminatory and sexist relationship that countries such as Canada have with highly skilled immigrant women is also a social justice and human rights violation issue. For instance, the expectation that they must possess Canadian experience is unjust as it denies access to the labour market on grounds that are not related to their abilities or sector in which they were trained. Furthermore, the Canadian labour market is strewn with systemic barriers, including those that discriminate on the basis of race and ethnicity and on the basis of where the credentials might have been acquired (Chatterjee 2015, Taylor, 2018).

The recommendations arising from research conducted in the present study are as follows:

- Assumptions and interventions based on gender and race need to undergo retrospection and rethinking in hiring and other management policies and practices (Taylor, 2018)

- Continued discussions of gendered and racialized experiences are essential so that labour market policies and practices are more inclusive aimed towards equal participation of immigrant women (Maitra, 2015).

- Call for acknowledgment of unequal power relations within institutions that reproduce sexism and racism. For instance, racialized immigrant women from racialized source countries despite being trained in professions associated with the highest incomes in the Canadian labour market (e.g., engineering) are still underpaid compared to non-visible minority, native-born Canadian men (Maitra, 2015).

- Call for further research to be conducted to address the overrepresentation of racialized immigrant women confined in feminized niches of low-paid, precarious work as opposed to having access to more meaningful employment opportunities (Senthanar, 2019).

- Management policies and practices need further review so that training (such as, workplace cultural and soft skills training) address sexist attitudes that immigrant women experience within masculine work cultures in many sectors such as, engineering and information technology so as to not reinforce dominant cultural views (Haque, 2014; Maitra, 2015).

Conclusion

The objective of the research in this study was to examine the impact of race and gender on the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada.

The research questions that served to guide the research in the study were:

- How does gender influence the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada?

- How does race affect the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada?

The Canadian labour market is strewn with systemic barriers, racialized and gendered power structures that affect the labour market realities of immigrant women in profound ways. This is reflected in the fact that immigrant women face greater challenges than immigrant men in the Canadian labour market. Regardless of their education and work experience, immigrant women and particularly racialized immigrant women are forced into gendered occupations characterized by low wages, little or no work benefits and job stability, with fewer opportunities for upward mobility. Most immigrant women work in jobs that do not fully utilize their skills and this leads to both deskilling and ghettoization within marginal occupations unrelated to their field of training and expertise. The literature review conducted in this study revealed that immigrant women are a heterogeneous group and their workplace experiences are unevenly shaped by factors such as class, education level, age, race, immigration stream, and official language fluency. Race and gender, however, have a particularly significant influence on the labour market position of immigrant women in Canada. Recommendations made in this study echo the voices of scholars and advocates to pave proactive ways of improving the position of immigrant women in the Canadian labour market.

Author: Rukmini Borooah Pyatt

Bibliography:

Acker, Joan. 2006. Class Questions, Feminist Answers. New York: Rowman Littlefield.

Behtoui, A., & Neergaard, A. (2010). Social capital and wage disadvantages among immigrant workers. Work, Employment and Society, 24(4), 761-779.

Behtoui, A., Boréus, K., Neergaard, A., & Yazdanpanah, S. (2017). Speaking up, leaving or keeping silent: racialized employees in the Swedish elderly care sector. Work, employment and society, 31(6), 954-971.

Bevelander, P., & Pendakur, R. (2014). The labour market integration of refugee and family reunion immigrants: A comparison of outcomes in Canada and Sweden. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(5), 689-709.

Boréus, K., & Mörekenstam, U. (2015). Patterned inequalities and the inequality regime of a Swedish housing company. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 5(4), 105-124.

Chatterjee, S. (2015). Rethinking skill in anti-oppressive social work practice with skilled immigrant professionals. British Journal of Social Work, 45(1), 363-377.

Creese, G., & Wiebe, B. (20 July 2009). ‘Survival employment’: Gender and deskilling among African immigrants in Canada. International Migration. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00531.x.

Flores, G. M. (2011). Racialized tokens: Latina teachers negotiating, surviving and thriving in a white woman’s profession. Qualitative Sociology, 34(2), 313-335.

Hanley, J., Al Mhamied, A., Cleveland, J., Hajjar, O., Hassan, G., Ives, N., & Hynie, M.

(2018). The social networks, social support and social capital of Syrian refugees privately sponsored to settle in Montreal: Indications for employment and housing during their early experiences of integration. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 50(2), 123-148.

Haque, E. (2014). Language training and labour market integration for newcomers to Canada. Liberating Temporariness? Migration, Work, and Citizenship in an Age of Insecurity.

Jagire, J. (2019). Immigrant Women and Workplace in Canada: Organizing Agents for Social Change. SAGE Open, 9(2), 2158244019853909.

Jeeva, A. (2018). Newcomer women and the workforce: A critical policy analysis of employment and labour legislation in Ontario.

Killian, C., & Manohar, N. N. (2016). Highly skilled immigrant women’s labor market access: a comparison of Indians in the United States and North Africans in France. Social Currents, 3(2), 138-159.

Kofman, E., & Raghuram, P. (2015). Gendered migrations and global social reproduction: an introduction. In Gendered migrations and global social reproduction (pp. 1-17).

Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Lubbe, W., ten Ham-Baloyi, W., & Smit, K. (2020). The integrative literature review as a research method: A demonstration review of research on neurodevelopmental supportive care in preterm infants. Journal of Neonatal Nursing.

Maitra, S. (2015). Between conformity and contestation: South Asian immigrant women negotiating soft skill training in Canada. Canadian Journal for the Study of Adult Education, 27(2 SE), 65-78.

Mears, C. (2010). A fine balance: Women, work and skilled immigration. Women’s Studies International Forum 33, 473-481.

Meraj, N. (2015). Settlement experiences of professional immigrant women in Canada, USA, UK and Australia.

Morrison, E. W., See, K. E., & Pan, C. (2015). An approach‐inhibition model of employee silence: The joint effects of personal sense of power and target openness. Personnel Psychology, 68(3), 547-580.

Ng, E. S., & Gagnon, S. (2020). Employment gaps and underemployment for racialized groups and immigrants in Canada: Current findings and future directions. Public Policy Forum.

Noack, A. M., & Vosko, L. F. (2011). Precarious jobs in Ontario: Mapping dimensions of labour market insecurity by workers’ social location and context. Toronto: Law Commission of Ontario.

Offermann, L. R., Basford, T. E., Graebner, R., Jaffer, S., De Graaf, S. B., & Kaminsky, S. E. (2014). See no evil: Color blindness and perceptions of subtle racial discrimination in the workplace. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(4), 499.

Panikkar, B., Woodin, M.A., Brugge, D., Hyatt, R., & Gute, D.M. (2014). Characterizing the low wage immigrant workforce: a comparative analysis of the health disparities among selected occupations in Somerville, Massachusetts. American journal of industrial medicine, 57 5, 516-26.

Panikkar, B., Woodin, M.A., Brugge, D., Hyatt, R., & Gute, D.M. (2014). Characterizing the low wage immigrant workforce: a comparative analysis of the health disparities among selected occupations in Somerville, Massachusetts. American journal of industrial medicine, 57 5, 516-26.

Premji, S., & Lewchuk, W. (2014). Racialized and gendered disparities in occupational exposures among Chinese and white workers in Toronto. Ethnicity & Health, 19(5), 512-528.

Premji, S., & Shakya, Y. (2017). Pathways between under/unemployment and health among raci lized immigrant women in Toronto. Ethnicity & health, 22(1), 17-35.

Senthanar, S. (2019). How do Syrian refugee women seek and find work? A feminist grounded analysis of work integration experiences in Canada

Senthanar, S., MacEachen, E., Premji, S., & Bigelow, P. (2020). “Can Someone Help Me?”

Refugee Women’s Experiences of Using Settlement Agencies to Find Work in Canada. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 21(1), 273-294.

Social Research and Demonstration Corporation (SRDC). (2019). Literature Review: Career Pathways for Visible Minority Newcomer Women in Canada.

Statista Research Department. (2021). Immigrant Women in Canada. https://www.statista.com. Accessed 3 January, 2022

Statistics Canada. 2016. Women in Canada: A gender-based statistical report. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Taylor, D. (2018). Flipping the script for skilled immigrant women: What suggestions might critical social work offer? RAIS Journal for Social Sciences, 2(1), 89-99.