The ‘Missing Middle’ | A Major Cause of Dwarfing of SMEs in Francophone Central Africa

The ‘Missing Middle’ is commonly defined as the gap in capital, which is larger than microfinance, yet smaller than traditional institutional financing like (commercial) banks in developing countries and emerging markets. An executive survey conducted in 2021 Q4 in Cameroon, revealed that only one SME out of fifty was launched using a bank loan. This represents only a 2% share of all surveyed SMEs. Although the survey showed that the share of bank-funded SMEs increased to 22% within the first five years of exercise and dropped to 12% after the first five years of exercise, the number of SMEs funded by banks in Cameroon remains quite low compared to other regions globally. This significantly encumbers SMEs’ growth in this African sub-region, causing formal businesses to dwarf, with 95% of the surveyed SMEs having, over years of exercise, a not-further-growing company size comprised between only 21 and 30 employees. This paper sheds light on the correlation between the ‘Missing Middle’ and the dwarfing of francophone Central African SMEs. It demonstrates that the ‘Missing Middle’ deprives SMEs of important financial backup needed to start and to foster business development activities. With this paper, the author pursues the objective of raising awareness and increasing incentives of bank funding for SMEs in the subregion.

Theoretical Framework

A thriving private business sector, largely led by SMEs, is essential for sustainable economic development in all countries (Olga, 2003). Many other authors like Ayyagari, Beck & Demirgüç-Kunt (2007), Dalberg (2011), and Lawal Aliyu (2018) echo this. The authors confirm that SMEs play a crucial role in spawning local, national, and sub-regional economy, while furthering growth, innovation (Von Drachenfels & Kraus, 2009), and prosperity. Yet, in Central Africa, SMEs struggle to survive, to grow (Evou, 2020).

One of the biggest hindrances of SMEs preventing these inescapable vectors of economic development to thrive has been reported to be low access to funding and rare or, at least, too high-interests bank loans (Evou, 2020). Especially SMEs, that belong to what is commonly referred to as the ‘Missing Middle’; do suffer from lack of finance to boost up their expansion activities (Von Drachenfels & Krause, 2009; International Finance Corporation, 2010; Hambayi, 2019). Among these activities are business development activities, which were shown to be overriding for the growth of an SME (Shobhit, 2020). Yet, business development activities require dedicated and consistent financial infusion, especially in the early stages of the SMEs, where the ROI is not reached yet, and the revenue does not suffice to cover all current expenses of the company (Kana Sonfack, 2022).

Bank lending could efficiently help here. However, banks seem to be reluctant to grant business loans to SMEs in Central Africa (DCA Africa, 2018), although the International Finance Corporation (2007) reported on average 28% higher operating incomes and 35% higher operating profits specifically for SME lending than for bank lending as a whole.

Withal, nothing has been published to date regarding the relationship between the stagnation of company size, partly caused by unfulfilled business development, and the ‘Missing Middle’ in francophone Central Africa particularly. Hypothesizing that both factors are entangled, this paper seeks to find out the nature of this relationship and to describe it.

The significance of this study lies in the fact that, by unveiling the correlation between the ‘Missing Middle’ and the dwarfing of SMEs in French-speaking Central African countries, stronger incentives can be initiated by local governments to enforce economic mechanisms that would make banks more prone to fund SMEs, thus boosting the sub-regional macroeconomics even stronger and so contributing to a much wealthier black continent.

Literature Review

Defining SMEs in the Context of Cameroon

What an SME in essence is, varies markedly from one continent to another and from one country to the other (Kana Sonfack, 2022). Gibson (2008) thus underlines how difficult it is to define an SME plainly and unanimously. Because it looks inappropriate and inaccurate to use an SME’s definition that does not match the surveyed country, the SME’s definitions of Zambo’s (2006) and Afriland First Bank (2015), which are specific to Cameroon, the model-country for this study, will be considered. The authors define an SME as a company employing between 21 and 100 employees, with a total annual turnover comprised between CFA 100,000,000 (about USD 181,446) and CFA 1,000,000,000 (about USD 1,814,463). Although this definition encountered significant hindrances and limitations on the research field, especially regarding the turnover, it was still relied on to randomly select the SMEs candidates to be surveyed in the context of this research study. Yet, only the companies’ sizes in terms of total number of employees were consequently taken into consideration in course of sample selection.

Defining the ‘Missing Middle’

The term ‘Missing Middle’ too has received diverse definitions in the past decade. For example, Oiko Credit (2020) defines it as the gap between microfinance institutions (that lend mostly to small, micro-enterprises of the informal sector) and traditional banks (which mostly lend money preferably to bigger companies that, considering their sizes and higher turnovers, are too big to count as SMEs in the context of Central Africa and particularly in Cameroon. DCA Africa (2018) defends that this term also refers to as ‘SME Finance Gap’ and seems to provide the most appropriate definition pertaining to it. They state that the ‘Missing Middle’ represents the gap in capital, which is larger than microfinance, yet smaller than traditional institutional financing through (commercial) banks in developing and emerging markets. Consequently, the clusters of companies in the middle, i.e., in the gap, typically the SMEs have no special type of financial institution that would preferably lend them the money they need to develop their activities through genuine business development.

SMEs’ Sustainable Growth is Coupled to Successful Business Development

Various authors demonstrated that the practice of sustainable and consequent business development bolsters better and healthier businesses, in the sense of increasing their overall growth (Johnson, Webber & Thomas, 2007), their innovation potential (Von Drachenfels & Krause, 2009), as well as their export records as found out by Bennett & Robinson (2003). These three factors of any business, when combined together, ensure success and thrive to any SME. However, achieving them require financial efforts that (early-stage) SMEs in francophone Central Africa very often do not have access to. Therefore, when business development activities cannot, or are only inefficiently or partly conducted, for example due to lack of funding or bank lending, SMEs tend to either not survive or to stagnate in size, thus dwarfing over time.

Current State of Bank Lending for SMEs in francophone Central Africa

Abel-Koch (2019) explains that access to finance is the main obstacle to SMEs in Africa. The works of the author exhibit that francophone Central Africa is the African sub-region where, as an SME, being funded by a bank is the most difficult in the whole continent. On their side, Banks, when questioned, do mention as a reason to their reluctance towards lending money to SMEs in the sub-region, that only few of the latter cope with fulfilling their credit requirements DCA Africa (2018). Madiefe Piabuo, Menjo Baye & Chupezi Tieguhong (2015) reported that interest rates, size of enterprise, size of loan, size of collateral, maturity of loans and legal status of enterprises are major sources of credit constraints faced by Cameroonian SMEs. They additionally indicate that among SMEs, medium enterprises are more credit-constrained than small enterprises, which emphasizes the ‘Missing Middle’ phenomenon even stronger. They finally stated that credit-constrained firms do display much lower levels of productivity and growth compared to unconstrained firms, a direct consequence of inexistent or unfulfilled business development.

Methodology

Research Design

This research study relied on a basic correlational design to study the correlation between the ‘Missing Middle’ and the dwarfing in size of SMEs in francophone Central Africa, on the example of Cameroon. The latter was chosen as a model-country for this study and was considered representative for the entire economic and financial region of francophone Central Africa not only because it is widely advocated in the literature that the country is a “miniature Africa” (Euronews, 2017), but also because it is the leading economy in the francophone Central African sub-region (Kum et al, 2019).

Method of Data Collection

An executive survey was conducted. The interviewed SMEs were randomly selected in different regions of the country. Furthermore, the SMEs’ population was selected notwithstanding their sectors of activity. All the SMEs selected were formally registered businesses operating in their respective markets since at least five years. These parameters were integrated to the selection process in order to ensure high representatives of the collected data. The second source of data was from diverse literature sources, from the internet, from journals, as well as from relevant business magazines and books.

Data Analysis and Presentation

Data Analysis

The data used for this research originated from responses received from the SMEs’ executives who we were able to interview. A total sample of 50 SMEs was approached, 25 of which had already gone bankrupted at least 5 years after the company’s creation, whilst the other half was composed of SMEs still in exercise since at least 5 years.

Data Presentation

The collected data are first presented in form of a table. The proportions computed were obtained using the simple percentage method, and the values were subsequently plotted in diagrams.

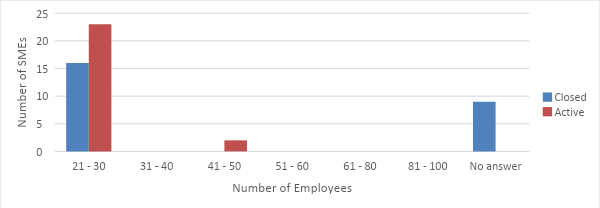

Data Presentation of the SMEs’ sizes

In this section, we present the data collected regarding the sizes (in number of employees) of the surveyed companies.

Table 4.1: SMEs by Number of Employees

|

SME activity status |

Range of number of employees |

||||||

|

21 – 30 |

31 – 40 |

41 – 50 |

51 – 60 |

61 – 80 |

81 – 100 |

No answer |

|

|

Closed / Bankrupt |

16 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

|

Still active |

23 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Based on this table, the following plot could be outlined.

Figure 4.1: Plot of SMEs by Number of Employees

“No answer”-candidates represent SMEs from which no answers regarding the interviewed executives knew the asked question.

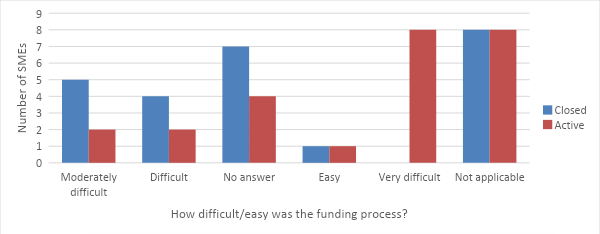

Data Presentation of How SMEs Perceive Their Chances to Get a Bank Loan

In this section, we present the data collected regarding how the interviewed companies evaluate the process of bank lending in the country.

Table 4.2: How SMEs Perceive the Process of Getting a Bank Loan in Cameroon

|

SME activity status |

How do you qualify the process of getting a bank loan in your country? |

|||||

|

Very difficult |

Difficult |

Moderately difficult |

Easy |

No answer |

Not applicable |

|

|

Closed / Bankrupt |

0 |

4 |

5 |

1 |

7 |

8 |

|

Still active |

8 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

8 |

“Not applicable” represents companies whose executives had never been at a bank with the purpose of applying for a business loan. They thus did not appear relevant for the purpose of this study. Based on these values, the following chart was plotted.

Figure 4.2: How SMEs Rate the Process of Getting a Bank Loan in Cameroon

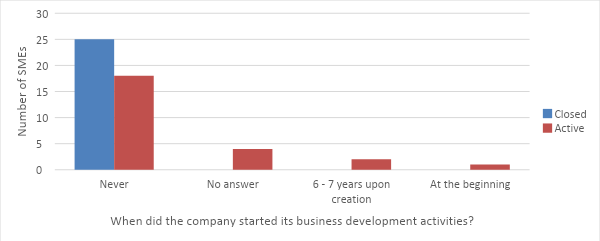

Data Presentation of When SMEs Started Their Business Development

In this section, the SMEs’ executives were asked when their business development activities started.

Table 4.3: Starting Time of Business Development Activities

|

SME activity status |

When did you start your business development activities? |

|||

|

Never |

Simultaneously to company creation |

6 to 10 years after creation of the company |

No answer |

|

|

Closed / Bankrupt |

25 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Still active |

18 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

These values led to the following graph.

Figure 4.3: When Do Cameroonian SMEs Start Their Business Development Activities

Interpretation of Data

The research data show that 39 SMEs out of 50, although (having been) active for more than 5 years, have not been able to grow their sizes over the range of 21 to 30 employees (Figure 4.1). Due to diverse reasons, 9 of the already bankrupt companies were not able of informing us about the exact number of employees the company had by the time it closed. Thus, we disregarded these samples and focused on the more informative ones. This led us to a total percentage of slightly more than 95% of Cameroonian SMEs not exceeding the range of 21 to 30 employees after years of exercise.

Regarding the accessibility of bank loans in the country, table 4.2 showed how SMEs’ owners do perceive the process of applying for (and eventually being successfully granted) a business loan at a traditional (commercial) bank. As already mentioned above, the “Not applicable” refers to companies whose executives had never been at a bank with the aim of applying for a business loan, whilst the “No answer”-candidates represent executives that explicitly gave us no answer to this question. Therefore, the total samples to be considered for analyzing this section had to be funneled to 10, for already closed companies, and to 13, for still active companies; for a total of 23 SMEs successfully and relevantly surveyed. Among these, nearly 35% considered the lending process as being “very difficult”, 26% saw it as “difficult”, 30% found it is “moderately difficult”, while only 4% of the executives said it was “easy” for them to get a business loan. The overall trend of these results reflects that the lending process in Cameroon is tedious and knotty for SMEs.

Figure 4.3 features how far SMEs have been able to conduct their business development activities in the country, or if at all they did it. Out of the 50 SMEs in the survey, 4 gave no answer to the question, thus reducing the total number of relevant samples to 46, of which 94% never started any consequent business development activities, only 2% started them right away after company creation, whereas 4% had to wait 6 to 7 years after the company creation to launch their business development activities. Interestingly, all 25 SMEs (i.e., 100% of the SMEs in this subcategory) that underwent bankruptcy, never started any business development activities.

Testing Hypothesis

In view of the above results, the initial hypothesis, which stated that SMEs in francophone Central African struggle to grow and dwarf in size because of the ‘Missing Middle’ caused by a lack or a rarefication of lending from traditional banks, was confirmed. Having no or only limited financial means at their disposition, these companies are not able to conduct genuine business development activities, which makes them stagnate over long years.

Conclusion

The existence of the ‘Missing Middle’ is detrimental to SMEs in the French-speaking Central African sub-region, although it has been recurrently demonstrated how important these economic organs are for the economic development of these countries. By not lending money to SMEs, sub-regionally operating banks prevent them from growing and expanding, thereby strangulating their huge potential to create even more wealth for the countries these firms operate in. Increasing incentives for banks to lend more easily the necessary money to bank can sustainably alleviate this problem and durably foster the economic growth of francophone Central Africa.

Author: Hermann Kana

References:

Abel-Koch, J. (2019), “Access to Finance is Main Obstacle for SMEs in Africa”, KfW Research, Economy in Brief, No 172, 17 January 2019

Afriland First Bank (2015), “Annual Report 2015”, retrieved 17.01.2022 from https://www.afrilandfirstbank.com/index.php/en/finacial-results/report2015

Ayyagari, M., Beck, T., and Demirgüç-Kunt, A. (2007), “Small and Medium Enterprises Across the Globe”, Small Business Economics, February 2007, s11187-006-9002-5

Bennett R.J. and Robinson P. (2003), “Changing Use of External Business Advice and Government Supports by SMEs in the 1990s”, Regional Studies; 37: 795-811

Dalberg (2011), “Report on Support to SMEs in Developing Countries Through Financial Intermediaries”, retrieved 19.07.2021 from Science Research: An Academic Publisher

DCA Africa (2018), “Investing in Africa: Defining the Missing Middle”, retrieved 17.01.2022 from http://www.dca-africa.com/site2018/saving-tips-from-scratch/

Euronews (2017), “Cameroun: l’Afrique en Miniature”, Euronews, retrieved 08.08.2021 from https://fr.euronews.com/next/2017/

Evou, J.-P. (2020), “Durée de Vie et Chances de Survies des PME au Cameroun”, Revue Économie, Gestion et Société, Nr. 22, Février 2020

Gibson, T., and Van der Vaart, H. J. (2008), “Defining SMEs: A less Imperfect Way of Defining Small and Medium Enterprises in Developing Countries”, Brookings Global Economy and Development, retrieved 20.07.2021 from brookings.edu

Hambayi, T. (2019), “Why the Future is African — And Why SMEs Should Lead the Way”, Guest Articles, retrieved 20.07.2021 from nextbillion.net

International Finance Corporation (2007), “Annual Report for the FY 2007”, retrieved 16.01.2022 from https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/publications

International Finance Corporation (2010), “Access to Finance: Annual Review Report 2010”, IFC Advisory Services, World Bank Group, retrieved 10.08.2021 from https://www.ifc.org/

Johnson, S., Webber, D. J., and Thomas, W. (2007), “Which SMEs use External Business Advice? A Multivariate Subregional Study”, Environment and Planning A, 39, 1981-1997

Kana Sonfack, H. (2022), “A Grounded Theory Approach to Foster Business Development in Central Africa”, unpublished dissertation thesis, Department of Business Administration, LIGS University, USA

Kum, F. V. et al. (2019), “The State of Small Business in Cameroon: SMEs, - Drivers for Job Creation and Employment in Cameroon”, Small Business and Entrepreneurship Center, Small Business Report, retrieved 20.07.2021 from nkafu.org

Lawal Aliyu, U. (2018), “Problems and Solutions of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Nigeria”, International Journal of Economics & Business, Zambrut, ISSN: 2717-3151, Volume 2, Issue 1, page 1 – 4

Madiefe Piabuo, S., Menjo Baye, F. and Chupezi Tieguhong, J. (2015), “Effects of Credit Constraints on the Productivity of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Cameroon”, TTRECED-CAMEROON, University of Yaoundé II, Biovesity International –Cameroon

Oiko Credit (2020), “Financing SMEs, the Missing Middle”, retrieved 17.01.2022 from https://www.oikocredit.coop/l/en/mailing2/archiveview/1477

Shobhit, S. (2020), “Business Development: The Basics”, retrieved 11.06.2021 from investopedia.com

Von Drachenfels, C. and Krause, M. (2009), “Fostering Economic Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: What Role for Reforming Regulations?”, Focus, CESifo Forum 4/2009.

Zambo, G. F. (2006), “Nature et Spécificités de L'entrepreneuriat Camerounais”, Université de Marne-La-Vallée - Master professionnel AIGEME (Application Informatique à la Gestion aux Etudes, au Multimédia et à l’E-formation) option internet, Mémoire Online